When should a post-occupancy evaluation by the facility manager be performed?

At the end of the correction period

Three to six months after initial occupancy

Just before the end of the warranty period

One year after substantial completion

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

CSI describes post-occupancy evaluation (POE) as a review of how the completed facility is performing for its users and operations staff, compared to the Owner’s Project Requirements (OPR). For the evaluation to be meaningful:

The facility must have been occupied long enough for systems and spaces to be used under normal operating conditions.

It should happen early enough that findings can inform warranty corrections, adjustments, and future projects.

CSI’s practice guidance indicates that POEs are typically performed several months after initial occupancy, often in the range of three to six months, when occupants have adjusted to the building and operational patterns are established but the project is still within the correction/warranty period. That aligns with Option B.

Why the others are less suitable:

A. At the end of the correction period and C. Just before the end of the warranty period – these are usually around one year; waiting this long reduces the time available to act on findings while warranties are in force.

D. One year after substantial completion – also generally coincides with warranty expiration; by then, significant issues may have already affected operations without being captured early.

Relevant CSI references:

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on facility management, occupancy, and post-occupancy evaluation.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – material on owner and facility manager activities during occupancy.

Which member of the project team initiates the project, assumes the risk, controls and manages the design and construction process, and provides the funding?

Contractor

Designer

Supplier

Owner

CSI’s description of project roles is very clear about the owner’s role in project delivery:

The owner is the party that:

Identifies the need or opportunity and therefore initiates the project.

Provides the funding for design and construction.

Retains the design and construction teams and selects the project delivery method.

Ultimately assumes the primary financial and project risk, because the owner is the one investing in and depending on the completed facility.

In contrast:

The designer (architect/engineer) is responsible for planning and design, preparing construction documents, and administering the construction contract on the owner’s behalf, but does not typically initiate the project or provide funding.

The contractor is responsible for constructing the project in accordance with the contract documents; the contractor bears construction execution risk, but not the basic project-initiative and funding role.

Suppliers provide materials/equipment and have no overarching control over the project delivery process.

The question lists all of the characteristics that CSI attributes to the owner:

“initiates the project, assumes the risk, controls and manages the design and construction process, and provides the funding.”

Thus, the correct answer is Option D – Owner.

CSI references (by name only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – “Participants in Project Delivery” (owner, designer, constructor, suppliers)

CDT Body of Knowledge – descriptions of owner responsibilities and risk

During the schematic design phase, a contingency line item in the estimate would be included to cover which of the following?

Allowances

Unit prices

Unknown factors

Alternates

In CSI-based project cost planning, contingency is defined as an amount added to an estimate or budget to cover uncertainties and unknowns that cannot yet be clearly defined at the current level of design development.

CSI’s practice guides and CDT materials explain (paraphrased):

In early design phases, such as schematic design, the design is only partially developed. Important elements are still undecided, and system configurations may change. Because of this, the cost estimate is inherently less precise.

A contingency line item is therefore included to cover:

Incomplete design information,

Potential scope refinement,

Normal estimating uncertainties, and

Other unknown factors at that stage.

As the project moves into design development and later into the construction documents phase, the design becomes more complete and the uncertainty decreases, so contingency percentages typically decrease.

By contrast, CSI differentiates contingency from other estimating tools:

Allowances: Specific sums in the contract for known-but-not-fully-defined items (e.g., “flooring allowance of X per m²”). These are identified items with placeholder values, not general unknowns.

Unit prices: Agreed rates for measuring work (e.g., $/m³ of rock excavation) used when quantities are uncertain, but scope categories are known and clearly described in the documents.

Alternates: Defined options requested by the owner (additive or deductive) for comparison and selection—again, specifically described items, not “unknowns.”

Because the question specifically references the schematic design phase and asks what the contingency line item covers, the CSI-aligned answer is “Unknown factors” – Option C.

Why the other options are incorrect:

A. Allowances – These are separate, explicit line items in the estimate or specifications and are not what contingency is intended to cover.

B. Unit prices – These deal with agreed rates for work whose quantities may vary, not with broad early-phase uncertainty.

D. Alternates – Alternates are specifically described choices requested for comparison; they are priced individually, not absorbed into contingency.

Key CSI-aligned references (no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on cost planning and contingencies by phase.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – definitions and uses of contingency, allowances, unit prices, and alternates in estimating.

An electrical engineer completes a set of electrical drawings and specifications for a project, except for the site electrical work which is indicated on the civil drawings. Which of the following is the intent of the contract documents?

The civil contractor is to place the concrete bases and the electrical contractor is to install the site lighting.

The civil contractor is to place the concrete bases and the site lighting, with the electrical contractor making the final connections.

The general contractor needs to coordinate the work and verify that the electrical subcontractor bids the site electrical.

The electrical engineer does not need to control how the work is to be assigned to subcontractors.

CSI’s core principle is that contract documents describe the work results required, not the internal means, methods, or subcontracting arrangements of the contractor. The contractor (or construction manager) is responsible for:

Determining how the work will be divided among trades and subcontractors.

Coordinating different trades to achieve the required results shown on the drawings and described in the specifications.

Design professionals (architects and engineers):

Organize the documents by disciplines and work results (e.g., civil, architectural, electrical), not by subcontractor or trade contract structure.

Are not responsible for dictating which subcontractor performs which portion of the work; that is the contractor’s role.

Given that:

Site electrical work appears on civil drawings, but the electrical engineer has also prepared electrical documents for the building systems.

The intent of the contract documents is still to describe what must be installed and how it must perform, not which subcontractor does it.

The only option that aligns with CSI’s stated roles and responsibilities is:

D. The electrical engineer does not need to control how the work is to be assigned to subcontractors.

Why the other options are not the “intent” of the documents:

A. The civil contractor is to place the concrete bases and the electrical contractor is to install the site lighting.This presumes a specific trade split based on drawing origin. CSI emphasizes that the contractor determines trade assignments, not the drawings themselves.

B. The civil contractor is to place the concrete bases and the site lighting, with the electrical contractor making the final connections.Again, this dictates trade assignments. The documents may show coordination between civil and electrical work, but do not prescribe how contractors must divide their subcontracts.

C. The general contractor needs to coordinate the work and verify that the electrical subcontractor bids the site electrical.While coordination of work is indeed a contractor responsibility, the phrasing here implies that the documents intend to direct which subcontractor must price which work package. CSI’s standpoint is that the contractor is free to structure subcontract bids as they see fit, as long as the required work is provided in accordance with the contract.

Thus, the intent of the contract documents is to define the required end results, not to assign work scopes among subcontractors. Option D correctly reflects that intent and the design professional’s role.

Relevant CSI-aligned references (no URLs):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – roles and responsibilities of owner, design professional, and contractor; explanation that contractor controls means, methods, and subcontracting.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – distinction between describing work results and assigning work trades.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – contract document intent vs. contractor’s responsibility for dividing the work.

What is MasterFormat® keyword index used for?

Identifying Level 4 sections

Identifying specification format

Locating subject titles and numbers

Specifying correct word usage

The MasterFormat® system, maintained by CSI and CSC, organizes work results into a numbered and titled hierarchical structure (Divisions, Level 2, Level 3, Level 4). Included with MasterFormat is a keyword index.

CSI describes the MasterFormat keyword index as a tool that:

Lists common keywords and subject terms used in construction (e.g., “gypsum board,” “elevators,” “unit masonry”).

Cross-references each keyword to the appropriate MasterFormat section number and title.

Helps specifiers and project team members find where a product, system, or topic belongs when writing or organizing sections.

Therefore, the keyword index is used for:

Locating subject titles and numbers – Option C.

Why the other options are incorrect:

A. Identifying Level 4 sectionsWhile the keyword index may point to Level 4 numbers, its purpose is not specifically to “identify Level 4 sections” but to locate the correct section number and title (at any level) based on subject words.

B. Identifying specification formatSpecification format (such as SectionFormat and PageFormat) is addressed in separate CSI standards, not by the MasterFormat keyword index.

D. Specifying correct word usageThe keyword index is not a language or style guide; it does not prescribe grammar or “correct word usage” in that sense. It is an indexing and locating tool for section numbers and titles.

Relevant CSI-aligned references (no URLs):

CSI / CSC MasterFormat® publication – introduction and explanation of keyword index function.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – discussion of using MasterFormat and its indexes to organize specifications.

CSI CDT Study materials – overview of MasterFormat and how to use the keyword index to locate topics.

As a project manager representing a private client, which of the following instances would best benefit from a constructability review meeting?

The client is unfamiliar with this type of project.

The project team consists of multiple new members.

The site presents unusual challenges and constraints.

The contractor is unable to commit to original schedule.

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation (CSI-aligned, paraphrased)

In CSI’s project delivery guidance, constructability reviews are described as a structured way to have construction-experienced professionals—often contractors, CMs, or experienced field personnel—review the design during planning or design phases to determine:

Whether the design can be built efficiently and safely

How site conditions, constraints, and logistics will affect means and methods

Potential cost, schedule, and sequencing issues arising from unique or complex aspects of the project

Constructability reviews are especially valuable when:

The site is constrained (tight urban sites, limited access, nearby sensitive structures)

There are unusual ground, environmental, or logistical conditions

The work involves complex staging, phasing, or access issues

Option C. The site presents unusual challenges and constraints is therefore the clearest trigger for a constructability review, because it directly ties to the need to evaluate how the physical and logistical realities of the site affect construction feasibility, cost, and sequence.

Why the other options are less appropriate:

A. The client is unfamiliar with this type of project.This calls for more owner education, clearer communication, and perhaps additional planning or programming support—not specifically a constructability review. The core need is understanding, not constructability.

B. The project team consists of multiple new members.That suggests a need for team alignment, clarification of roles, and communication protocols. While new team members may benefit from constructability input, the main justification for a formal constructability review is project/site complexity, not simply team turnover.

D. The contractor is unable to commit to original schedule.This is a procurement or scheduling problem, often addressed through rescheduling, negotiation, or possibly re-bid. Constructability reviews are proactive during design; schedule commitment issues often arise later and are handled with different tools (e.g., schedule analysis, changes, resequencing).

Key CSI-Related References (titles only):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on constructability reviews and preconstruction services.

CSI CDT Study Materials – discussions of preconstruction evaluation, constructability, and risk identification.

When does a project reach substantial completion?

When the project is sufficiently complete to allow its intended use

When the project receives final inspections from the authorities having jurisdiction

When the contractor's final application for payment is approved

When all of the close-out documents have been reviewed and approved

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation (CSI-aligned, paraphrased)

CSI and commonly used general conditions define Substantial Completion as the stage in the progress of the Work when:

The Work, or a designated portion, is sufficiently complete in accordance with the Contract Documents so that the Owner can occupy or utilize it for its intended use.

Important implications in CSI/CDT context:

Substantial Completion is a functional milestone, not simply an administrative or paperwork milestone.

At Substantial Completion:

The Owner can begin using the facility for its intended purpose (e.g., occupy offices, treat patients, teach classes).

The warranty periods typically begin, unless otherwise specified.

The responsibility for utilities, security, and insurance often shifts in whole or in part to the Owner.

Final inspections, final payment, and complete closeout documentation generally occur after Substantial Completion.

So the correct definition is:

A. When the project is sufficiently complete to allow its intended use.

Why the other options are not correct:

B. When the project receives final inspections from the authorities having jurisdiction – AHJ inspections (for occupancy permits, etc.) are important and often coincide with or enable Substantial Completion, but they are regulatory milestones, not the contractual definition itself. Substantial Completion is determined under the contract, usually via certification by the A/E.

C. When the contractor’s final application for payment is approved – That is associated with Final Completion, which occurs after all work (including punch list) is done and all closeout requirements are met. Substantial Completion occurs before final payment.

D. When all of the close-out documents have been reviewed and approved – Closeout submittals (O&M manuals, warranties, as-builts) are typically prerequisites for final payment and Final Completion, not for Substantial Completion.

Key CSI-Related Reference Titles (no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on Construction Phase, Substantial Completion, and Final Completion.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Division 01 “Closeout Procedures” and “Substantial Completion” articles.

CSI CDT Study Materials – definitions of Substantial and Final Completion.

Under SectionFormat®, where would the Article "Manufacturers" be found?

Either Part 1 or Part 2

Part 1 only

Part 2 only

Part 3 only

CSI’s SectionFormat® establishes a standard three-part structure for specification sections:

Part 1 – GeneralAdministrative and procedural requirements specific to that section (scope, related work, references, submittals, quality assurance, delivery/storage, warranties, etc.).

Part 2 – ProductsDescriptions of products, materials, and equipment required: manufacturers, materials, components, fabrication, finishes, performance requirements, and similar.

Part 3 – ExecutionField/application/installation requirements: examination, preparation, installation/application procedures, tolerances, field quality control, adjustment, cleaning, protection, etc.

Within this structure, CSI specifically places “Manufacturers” as an article in Part 2 – Products. This is because Part 2 is where the specifier identifies:

Acceptable manufacturers or manufacturer list

Standard products and models

Performance or quality requirements associated with those manufacturers

Product substitutions (if addressed by article structure)

Placing “Manufacturers” in Part 2 maintains consistency across specs and makes it clear that manufacturer-related information is part of the product requirements, not administrative conditions or execution procedures.

Why the other options do not align with SectionFormat®:

A. Either Part 1 or Part 2Although some poorly structured sections in practice may misplace content, CSI’s recommended SectionFormat® is explicit: manufacturers belong in Part 2 – Products. Allowing Part 1 or Part 2 would blur the distinction between administrative requirements and product requirements.

B. Part 1 onlyPart 1 is not intended for listing manufacturers. It covers general/administrative topics, not the specific products or manufacturers.

D. Part 3 onlyPart 3 deals with execution/installation in the field, not who manufactures the products. Manufacturer listing in Part 3 would conflict with CSI’s structure and make the section harder to interpret and coordinate.

Therefore, under SectionFormat®, the correct location for the “Manufacturers” article is Part 2 only (Option C).

Key CSI References (titles only, no links):

CSI SectionFormat® and PageFormat™ (official CSI format document).

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – chapters explaining the three-part section structure and where to place specific articles such as “Manufacturers.”

CSI MasterFormat®/SectionFormat® training materials used for CDT preparation.

When preparing their bid, a contractor organizes their costs into different categories. The following items are examples of which type of cost?

Permits and inspections

Mobilization and startup

Jobsite safety and security procedures, including personnel

Administrative costs attributable to the work

Construction

Contingency

Overhead

Insurance

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

CSI’s estimating and bidding guidance divides project costs into:

Direct (construction) costs – labor, materials, equipment directly incorporated into the work.

Indirect costs / Overhead – project overhead (jobsite-specific) and home-office overhead.

Contingencies and profit.

The items listed in the question are classic examples of project (jobsite) overhead costs:

Permits and inspections – required to enable the work but not physically part of the building.

Mobilization and startup – moving equipment, setting up trailers, temporary utilities.

Jobsite safety and security procedures – safety staff, fencing, lighting, etc.

Administrative costs attributable to the work – site management staff, office supplies, communications.

These are necessary to execute the project but are not directly installed in the construction work, so they are categorized as overhead, making Option C correct.

Why others are incorrect:

A. Construction – refers to direct, installed work (concrete, steel, finishes, etc.), not these support functions.

B. Contingency – covers unknowns and risks; it is separate from known overhead items.

D. Insurance – is a specific cost category (builder’s risk, liability, etc.), distinct from the listed overhead activities, even though it may sometimes be grouped in “General Conditions” in a detailed estimate.

Relevant CSI references:

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – chapters on cost planning and estimating.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – sections on types of project costs (direct, indirect/overhead, contingency, profit).

Which Uniform Drawing System (UDS) symbol would be used in a plan view drawing and directs the user to an elevation view?

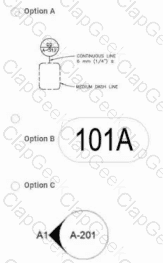

c

Option A – a symbol showing a circle with leadered detail and line-type notes

Option B – an oval with “101A” (room or space tag)

Option C – a circular symbol with a triangular pointer and text such as “A1” over “A-201”

Option D – a small cross with a leader to a box labeled “EL”

In the CSI Uniform Drawing System (UDS), now incorporated into the National CAD Standard, specific symbols are defined to link one drawing to another and to distinguish between types of referenced views (sections, details, elevations, etc.).

An elevation reference symbol placed in a plan view:

Identifies that an elevation drawing exists elsewhere,

Indicates which elevation it is (view or detail number), and

Indicates on which sheet that elevation is drawn.

The typical UDS elevation callout symbol is a circle with a pointer/triangle indicating the direction of view, with two fields of text: the view or detail identifier (e.g., “A1”) and the sheet number (e.g., “A-201”). That matches Option C: a circular symbol, with a black “wedge” or triangular pointer indicating the direction the elevation is looking, text such as “A1” near the pointer, and “A-201” within or adjacent to the circle showing the sheet where the elevation view is found.

Why the other options are incorrect:

Option A – This resembles a detail/section marker or a generic callout with line-type notes, not the standard UDS symbol for an elevation view referenced from plan.

Option B – An oval with “101A” is characteristic of a room or space tag (identifying room number, sometimes with occupancy or area), not a cross-reference to another drawing. It does not direct the user to any elevation view.

Option D – The small cross with a leader to a rectangle labeled “EL” is the UDS-type symbol for a spot elevation or elevation note, giving the vertical level of a specific point (e.g., top of slab at Elev. 103.50). It indicates a numeric elevation value, not a separate elevation drawing elsewhere in the set.

According to CSI’s UDS, the symbol used in plan that directs the user to an elevation view on another sheet is the elevation reference/callout symbol, represented by Option C.

Which of these is NOT a graphical format used to establish order and organization of construction drawings?

United States National CAD Standard

American Institute of Architects (AIA) CAD Layer Guidelines

Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) Uniform Drawing System

MasterFormat®

CSI’s various classification and formatting standards serve different purposes, and CDT content draws clear distinctions between them:

The United States National CAD Standard (NCS) and the AIA CAD Layer Guidelines (now part of NCS) define graphic conventions, sheet organization, layering, and symbols for CAD drawings.

The CSI Uniform Drawing System (UDS) (now integrated into the NCS) provides consistent formats and conventions for construction drawings, including sheet organization, drawing set organization, schedules, notation, and symbols.

All three—NCS, AIA CAD Layer Guidelines, and CSI UDS—are associated with graphical and organizational standards for construction drawings.

By contrast:

MasterFormat® is CSI’s specification and work-results classification system, which organizes information primarily into Divisions and Sections for specifications and other written documents, not drawings. CDT materials repeatedly emphasize that MasterFormat is used to organize project manual content and other written construction information, not the graphical content of the drawings.

Therefore, the one item not used as a graphical format for organizing drawings is:

D. MasterFormat®

Why the other options are correct as “graphical” or drawing-related formats:

A. United States National CAD Standard – Provides a nationally coordinated standard for CAD drawing presentation, including layering, symbols, and sheet organization.

B. AIA CAD Layer Guidelines – Define standard layer naming and structure for CAD drawings; these are explicitly about how graphical information is organized in electronic drawings.

C. CSI Uniform Drawing System – Developed to standardize the organization and graphical conventions of drawings, later integrated into NCS.

Thus, from a CSI standpoint, MasterFormat® is the outlier here: it organizes written construction information, not graphical drawing formats, making Option D the correct choice.

Which document directly modifies the requirements of the general conditions?

Division 01, General Requirements

Supplementary Conditions

Agreement

Instructions to Bidders

In the standard organization of the contract documents as taught in CSI’s CDT materials and practice guides, the General Conditions establish the baseline contractual rights, responsibilities, and relationships among the owner, contractor, and architect/engineer (A/E).

CSI explains that whenever there is a need to change or add to the standard provisions of the General Conditions (for example, to address project-specific insurance limits, bonding, liquidated damages, or local legal requirements), those changes are made in the Supplementary Conditions. The Supplementary Conditions are expressly written to modify, delete, or add to the printed General Conditions, and they do so by direct reference to specific articles or paragraphs.

The General Conditions set the standard, overall rules of the contract.

The Supplementary Conditions are the only document whose primary purpose is to modify those General Conditions for the specific project.

Other documents (Agreement, Division 01) must be consistent with the Conditions of the Contract but are not the formal instrument intended to “directly modify” the General Conditions.

Why the other options are not correct:

A. Division 01, General Requirements – Division 01 coordinates administrative and procedural requirements for the work and bridges from the Conditions of the Contract to the technical specifications. It may elaborate how procedures are implemented but it is not the document that directly amends the General Conditions.

C. Agreement – The Agreement (e.g., AIA A101) identifies parties, contract sum, contract time, and incorporates the Conditions, drawings, and specifications by reference. It relies on the General and Supplementary Conditions; it does not systematically edit their language.

D. Instructions to Bidders – These govern the procurement phase only (how to submit bids, qualifications, bid security, etc.) and cease to have effect once the Contract is executed. They do not modify the General Conditions of the construction contract.

CSI’s Project Delivery and Construction Specifications Practice Guides describe this hierarchy and emphasize that Supplementary Conditions are the proper instrument for project-specific modifications to the General Conditions, which makes Option B the correct answer.

What is the procedure for guarding against defects and deficiencies before and during the execution of the work?

Quality assurance

Quality control

Quality management

Quality monitoring

CSI distinguishes clearly between quality assurance (QA) and quality control (QC):

Quality assurance focuses on procedures, planning, and processes established before and during the work to prevent defects and deficiencies. It’s proactive and process-oriented—things like qualifications, mock-ups, preinstallation conferences, submittal review, and establishing methods.

Quality control focuses on inspection, tests, and verification of completed or in-progress work to identify defects and verify that requirements are met. It is more reactive and product-oriented.

The question asks for the procedure for guarding against defects and deficiencies before and during execution of the work, which clearly points to quality assurance—the preventive system of checks and requirements set up in advance and applied as the work proceeds.

Therefore, Option A – Quality assurance is correct.

Why the other options are not correct:

B. Quality control – QC is about testing and inspection of the finished or in-progress work to detect defects, not primarily about guarding against them through advance procedures.

C. Quality management – This is an overarching concept that can include both QA and QC but is not the specific procedural term CSI uses in the documents and Division 01 sections.

D. Quality monitoring – Not a standard CSI technical term in the same formal sense as quality assurance and quality control.

Key CSI-Oriented References (titles only, no links):

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – sections on “Quality Requirements” and the distinction between QA and QC.

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – Design and Construction Phase quality processes.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – “Quality Requirements in Division 01 and Technical Sections.”

Who is responsible for job site security?

Owner

Architect/engineer

Contractor

Construction manager

Under CSI’s project delivery framework and the typical General Conditions of the Contract, the contractor has primary responsibility for:

The means, methods, techniques, sequences, and procedures of construction.

Job site safety and security, including protection of workers, the public, and the work itself.

Controlling access to the site, securing materials and equipment, and complying with safety laws and regulations.

CSI’s CDT materials summarize the allocation of responsibilities this way (paraphrased):

The owner is responsible for providing information, funding, and overall project requirements; the owner does not direct day-to-day site operations or security.

The architect/engineer is responsible for design and contract administration functions such as reviewing submittals, certifying payments, and evaluating change requests—not for job site security or safety control.

The contractor (or construction manager acting as contractor, where applicable) is the party who controls the site and is therefore responsible for job site safety and security.

Even when a construction manager is involved (Option D), CSI and standard general conditions distinguish between a CM as advisor (who advises the owner) and a CM as constructor (who is essentially the contractor). For the exam-style question as written, “contractor” is the single correct generic answer for who is responsible for job site security.

Why the other options are not correct:

A. Owner – The owner does not direct means and methods or daily site activities; shifting site security responsibility to the owner would contradict the usual conditions of the contract.

B. Architect/engineer – The A/E does not control the job site and is not responsible for job site safety/security; this is a repeated CDT exam emphasis to avoid misallocating liability.

D. Construction manager – Only in specific project delivery methods where the CM is also the constructor (CM-at-Risk) does this role overlap with the contractor. The question’s general form points to the contractor as the standard answer in CSI’s framework.

Therefore, in accordance with CSI’s explanation of roles and responsibilities under standard conditions of the contract, the contractor is responsible for job site security, making Option C correct.

For a large transportation project, 53 borings were made and only one boring showed some contamination. Due to financial constraints, the owner is unable to provide additional funding to the design team for further investigation. Which of the following is the best course of action for the design team?

Withhold the information from the bid package because the full extent remains unknown. Ask bidders to provide a unit cost for remediation.

Provide a disclaimer on the contract documents about potential contaminants onsite and suggest the owner make the geotechnical report available to all bidders.

Insist the owner undertake additional investigation to determine the full extent prior to putting the project out for bid.

Proceed with design as is without any modifications since the results are statistically insignificant (i.e., well within expected deviations).

CSI’s project delivery and ethical guidance (as reflected in CDT materials and standard practice) emphasize:

Known information that may affect cost, risk, or safety must be disclosed consistently and fairly to all bidders.

The design professional must act in a manner that is honest, transparent, and protective of public safety, even when data is incomplete.

The bid documents should not conceal information that could materially affect the work, even if its full extent is uncertain.

Applying those principles:

The design team has evidence (one contaminated boring) that contamination may exist onsite. Even if the extent is unknown, that fact is potentially material to bidders (cost of remediation, handling of contaminated soils, schedule impacts).

The best course is to disclose what is known and ensure all bidders have access to the same geotechnical information. This is exactly what Option B proposes:

Place a clear note or disclaimer in the contract documents stating that contaminants were encountered in at least one boring and may be present elsewhere.

Recommend that the owner make the geotechnical report available to all bidders, so every bidder can evaluate the risk and price accordingly.

Why the other options are inconsistent with CSI-aligned practice:

A. Withhold the information… – Concealing known contamination is unethical and undermines fair bidding. Even with unit prices for remediation, bidders would be pricing blindly without knowing that contamination has already been detected.

C. Insist the owner undertake additional investigation… – While the design team should recommend further investigation, it cannot “insist” beyond professional advice, especially where the owner has clearly stated financial constraints. Regardless, disclosure of existing data is still required.

D. Proceed with design as is… – Ignoring known contamination and calling it “statistically insignificant” is not defensible; even one contaminated boring is important information that must be shared.

So, the most appropriate and CSI-consistent choice is Option B: disclose the potential and share the geotechnical report so all bidders are equally informed.

CSI references (by name only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on procurement, fair competition, and disclosure of information

CDT ethics and professional conduct principles regarding risk disclosure to bidders

What requirement is set by authority, custom, or general consensus that is also an established accepted criterion?

Building code

Quality control standard

Reference standard

Specification master

CSI’s terminology for specifications includes the concept of a “reference standard”, which is:

A requirement established by a recognized authority, by custom, or by general consensus.

An accepted criterion used to define properties, performance, or methods for materials, products, or workmanship (e.g., ASTM, ANSI, ACI, AISC, UL).

Cited in specifications so that, instead of repeating technical details, the spec simply references the named standard.

This is exactly the definition implied by the phrase “requirement set by authority, custom, or general consensus that is also an established accepted criterion.” That is the CSI definition of a standard, and in specification-writing context, specifically a reference standard. Hence the correct choice is C.

Why not the others:

A. Building code – A building code is a legal document adopted by public authority and enforced by the authority having jurisdiction; it is one type of regulatory document but not the generic term used in CSI for “established accepted criterion” used as a reference in specs.

B. Quality control standard – Quality control is a process; standards may be used within QC, but “quality control standard” is not the CSI term that matches this specific definition.

D. Specification master – CSI refers to master guide specifications or master specifications, but this is a spec-writing resource, not the formal term for a requirement established by authority or consensus.

CSI-aligned references (no URLs):

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – explanations of standards and reference standard method of specifying.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – definitions of “standard” and “reference standard” in the context of specifications.

You are working on a project that is subject to regulatory reviews both at the city and at the state level. Both agencies have acknowledged receiving the construction documents. This project has already been awarded to a general contractor, and you are representing the owner who wants to start construction immediately. How would you advise the owner?

Construction may begin immediately as long as a safety manager is present, and the contractor avoids all excavation work until after the permits are issued.

Since the state approval is more critical than the city approval, construction may proceed immediately after the state permits are issued.

Since the city approval is more critical than the state approval, construction may proceed immediately after the city permits are issued.

Construction may begin only after both city and state permits have been issued.

Under CSI’s project delivery and contracting principles, the contract documents are only one part of the legal framework that governs construction. Regulatory approvals and permits are a separate, critical requirement that must be satisfied before construction begins, regardless of contract award or the owner’s desire to proceed.

Key CSI-aligned concepts:

Building codes and other regulations are enforced by authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs)—in this case, both city and state agencies.

The owner, often via the design professional, must obtain the required permits from all AHJs before construction activities are started.

Contract award to a general contractor does not authorize construction to proceed without permits; doing so exposes the owner and contractor to violations, stop-work orders, penalties, and liability.

Therefore, the correct advice in a CSI-consistent framework is:

Construction may begin only after both city and state permits have been issued. (Option D)

Why the other options are incorrect:

A. Construction may begin immediately … if a safety manager is present and excavation is avoided.Safety management and the type of work do not override permit requirements. Work without required permits is typically prohibited regardless of safety measures.

B. Since the state approval is more critical … proceed after the state permits are issued.CSI acknowledges that all applicable jurisdictions must be satisfied. One jurisdiction is not “more critical” such that the other can be ignored. If both city and state approvals are required, the project must have both before construction starts.

C. Since the city approval is more critical … proceed after city permits are issued.Same issue as B. If both city and state have regulatory authority, both sets of permits are required; neither is optional or subordinate in this sense.

CSI-aligned references (no external links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on regulatory requirements and authorities having jurisdiction.

CSI CDT Study materials – discussions of permits, code compliance, and the relationship between AHJ approvals and the start of construction.

Typical General Conditions of the Contract as discussed in CSI materials – provisions requiring compliance with laws, codes, and permits.

Which meeting is held for the purposes of introducing the design and construction teams, establishing the ground rules for communication, and explaining the administrative process?

Mobilization meeting

Preconstruction meeting

Prebid meeting

Coordination meeting

In CSI’s project delivery framework, the preconstruction meeting (often called the preconstruction conference) is a formal meeting held after award of the construction contract and before substantial field work begins. Its typical purposes match the stem of this question almost word-for-word:

Introduce the key members of the owner’s team, the design team, and the contractor’s team.

Review and establish communication protocols – who communicates with whom, in what format (letters, emails, RFIs, submittals), and through which channels (e.g., via the A/E as the owner’s representative).

Explain administrative procedures for submittals, RFIs, change orders, applications for payment, project meetings, record documents, and closeout requirements.

Clarify roles and responsibilities, lines of authority, and decision-making processes during construction.

Review the project schedule, major milestones, site logistics, and constraints so everyone begins the project with a common understanding.

These points are fully consistent with how CSI’s Project Delivery Practice Guide and typical Division 01 “Project Management and Coordination” sections describe the preconstruction conference: as the kickoff meeting for the construction phase, focused on communication, procedures, and administration—not bidding or detailed technical coordination.

Why the other options are not correct:

A. Mobilization meeting“Mobilization” refers to the contractor’s process of moving onto the site (bringing in equipment, setting up field offices, etc.). While a project might have discussions about mobilization, “mobilization meeting” is not the standard CSI project-delivery term for this formal kickoff. The structured, procedure-focused meeting described in the question is the preconstruction meeting.

C. Prebid meetingA prebid meeting (pre-bid conference) occurs during procurement, before bids are submitted. Its primary purposes are to familiarize prospective bidders with the project, review procurement requirements, visit the site, and answer questions that might affect bids. It does not introduce the already-selected construction team, nor does it establish the project’s communication and administrative procedures for contract execution. That occurs after award in the preconstruction meeting.

D. Coordination meetingCoordination meetings are typically recurring, working meetings during construction to resolve ongoing technical, scheduling, or coordination issues between trades (e.g., MEP coordination). They do not serve as the initial, formal kickoff to introduce teams and set overall administrative and communication “ground rules.”

Therefore, the meeting that introduces the design and construction teams, sets communication ground rules, and explains administrative processes is the Preconstruction meeting (Option B), as aligned with CSI project delivery and Division 01 practices.

Key CSI References (titles only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – chapters on Construction Phase and Project Meetings (Preconstruction Conference).

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – discussions of Division 01 “Project Management and Coordination” and required project meetings.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – topic area: “Construction Phase Services and Communication.”

Which of the following establishes a baseline from which deviations are identified?

General requirements

Supplementary conditions

Project manual

General conditions

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-Based)

According to the Construction Specifications Institute (CSI) and CDT exam content, the General Conditions of the Contract form the foundational “baseline” set of administrative, procedural, and legal requirements for every construction contract. All other contracting documents—including Supplementary Conditions, Division 01, and specification sections—are modified in relation to this baseline.

Why the Correct Answer Is General Conditions (Option D)

CSI practice guides describe the General Conditions as:

The standard baseline document for project relationships, responsibilities, rights, and procedures.

The “default” set of requirements unless modified by Supplementary Conditions or Division 01.

The document against which all deviations must be clearly identified, especially when supplementary or project-specific requirements alter the standard conditions.

General Conditions define or baseline:

Roles and responsibilities of owner, contractor, A/E

Contract time, payments, changes, submittals, inspections

Dispute resolution

Site conditions, insurance, and protection of work

CSI emphasizes that the General Conditions do not change for each project unless Supplementary Conditions modify them, which reinforces that they form the baseline.

Why the Other Options Are Incorrect

A. General Requirements (Division 01)

Division 01 sections coordinate the administrative and procedural requirements for the project, but they expand upon or modify the General Conditions—not the other way around. They cannot be the baseline because they themselves rely on the baseline established in the General Conditions.

B. Supplementary Conditions

These modify the General Conditions to address project-specific legal or regulatory requirements (e.g., bonding, liquidated damages, insurance). They create deviations, not the baseline from which deviations are identified.

C. Project Manual

The Project Manual is a collection of documents—including bidding requirements, contract forms, General Conditions, Supplementary Conditions, and specifications. It is not itself the baseline; it contains the baseline (the General Conditions).

Key CSI References

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – Chapters on Procurement and Contracting, discussing General Conditions as the base document for rights, responsibilities, and procedures.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Sections on Contract Documents hierarchy and coordination.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – Contractual relationships and use of General Conditions as baseline documents.

Cost classification, data organization, and specifications use which written formats?

OmniClass and UniFormat

UniFormat and MasterFormat

OmniClass and MasterFormat

SectionFormat® and MasterFormat

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

CSI distinguishes among several written formats, each with a specific purpose:

UniFormat – organizes information by systems and assemblies (elements) and is commonly used for:

Cost classification and early cost estimating,

Data organization in the programming, schematic design, and design development stages.

MasterFormat – organizes information by work results (trades/products) and is used for:

Project specifications,

Detailed cost information tied to specification sections,

Organizing procurement and construction information.

CSI’s practice guides clearly connect cost classification and data organization in early design with UniFormat, and detailed specifications and later-stage cost information with MasterFormat. Therefore, the correct pair is:

UniFormat and MasterFormat (Option B)

Why the other options are incorrect:

A. OmniClass and UniFormat – OmniClass is a broader classification system for the built environment, not the primary written format CSI assigns to “specifications.” UniFormat is used for cost and systems, but OmniClass is not the standard format for specs.

C. OmniClass and MasterFormat – Again, OmniClass is overarching; it does not replace UniFormat as the main element-based cost classification tool.

D. SectionFormat and MasterFormat – SectionFormat is the internal three-part structure of a specification section (Parts 1, 2, and 3) and is not the format used for cost classification and data organization; that role is assigned to UniFormat.

Relevant CSI references (paraphrased):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – descriptions of UniFormat use for system-based project descriptions and cost planning, and MasterFormat use for work result organization.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – chapters on MasterFormat, UniFormat, and their roles in specifications and estimating.

Which type of warranty is used to provide a remedy to the owner for material defects or failures after completion and acceptance of construction?

Warranty of title

Implied warranty of merchantability

Purchase warranty

Extended warranty

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

CSI’s treatment of warranties in construction distinguishes among several types, including:

Warranty of title – assures that the seller/contractor has good title to goods and that they are free of liens or claims.

Implied warranties – such as merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, arising under applicable law for goods.

Express warranties – explicitly stated in the contract documents or manufacturer literature, which may include extended warranties.

In the construction context, CSI’s project delivery and specification guidance emphasizes that extended warranties (often called special warranties in specifications):

Survive completion and acceptance of the project.

Provide remedies to the owner for defects in materials and/or workmanship that appear after substantial completion, often beyond the standard one-year correction period.

Are commonly used for critical building components (e.g., roofing systems, waterproofing, major equipment) and may run for 5, 10, or more years.

This directly matches the question’s language: a warranty “used to provide a remedy to the owner for material defects or failures after completion and acceptance of construction.” That is precisely the purpose of an extended warranty in CSI-style contract documents and specifications, making Option D correct.

Why the other options are incorrect:

A. Warranty of titleThis deals with ownership and freedom from liens, not performance of materials or systems after completion. It does not address post-completion material defects.

B. Implied warranty of merchantabilityThis is a legal concept for goods: that they are fit for ordinary purposes. While it may apply in background law, it is not the specific contractual tool that owners rely on in construction documents to secure long-term remedies for material defects.

C. Purchase warranty“Purchase warranty” is not a standard CSI-defined category of construction warranty. Product or manufacturer warranties may be obtained at purchase, but the CSI terminology used in specifications and project delivery guidance is typically standard warranty, special warranty, or extended warranty, not “purchase warranty.”

Key CSI References (titles only):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on Warranties, Guarantees, and the Correction Period.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – guidance on specifying warranties (including extended warranties) in Division 01 and technical sections.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – “Contract Provisions: Warranties and Guarantees.”

When innovative or unusual design techniques are proposed, it is advised to have what type of review?

Sustainability

Budget

Constructability

Design

CSI materials emphasize that constructability reviews (often performed by experienced contractors or construction managers) are highly valuable when a project involves:

Innovative systems or unusual details

Complex sequencing or temporary works

Tight site constraints or aggressive schedules

A constructability review examines whether the design can be built safely, efficiently, and economically, considering available means and methods, typical trade practices, site access, sequencing, and risk. When a design uses innovative or unusual techniques, there is more risk that something may be difficult or impractical to build. CSI and CDT guidance recommend obtaining feedback from construction professionals at that stage.

Why the correct answer is C. Constructability:

The purpose of the review is to assess the buildability of the proposed design: how it will actually be constructed, staged, sequenced, supported, and coordinated among trades. This is exactly what a constructability review is intended to do.

Why the other options are not the best answer:

A. Sustainability – A sustainability review may be appropriate for environmental performance (energy, materials, certifications) but is not specifically focused on making sure an unusual design technique can be constructed.

B. Budget – A budget review checks cost impacts, which is important but does not by itself determine whether the technique is actually constructible.

D. Design – “Design review” is a very broad term and happens continuously. The question is specifically about innovative or unusual design techniques and what type of review is recommended. CSI guidance specifically names constructability review in this context.

Relevant CSI / CDT References (titles only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on “Programming and Design Phases,” and the role of constructability reviews.

CDT Body of Knowledge – topics on early involvement of construction expertise and constructability reviews.

During the bid period, what does the architect issue if it is necessary to modify the procurement documents?

Addenda

Construction change directives

Change order

RFI response

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-aligned, paraphrased)

CSI distinguishes clearly between procurement-phase modifications and construction-phase changes:

During procurement (bidding/negotiation), the documents used for pricing and proposing work are called procurement documents (instructions to bidders, bid forms, drawings and specifications issued for bid, etc.).

If these need to be clarified, corrected, or modified before bids are received, the architect/engineer issues an addendum.

An addendum:

Is a written or graphic modification to the procurement documents issued before the execution of the contract.

Becomes part of the procurement documents and, once the contract is formed, part of the contract documents.

Must be issued to all known prospective bidders to maintain fairness and keep everyone pricing the same requirements.

By contrast:

Construction Change Directive (CCD) and Change Order are used after the contract is executed, to modify the contract documents during construction (scope, cost, or time).

An RFI response answers a bidder’s or contractor’s question, but if the answer changes the procurement/contract requirements, it must be formalized by addendum (before award) or change order/CCD (after award), not just left as an informal answer.

Therefore, the correct instrument during the bid period to modify procurement documents is:

A. Addenda

Key CSI-Related References (titles only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – chapters on Procurement, Addenda, and pre-award communications.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Division 00 discussions of Instructions to Bidders and Addenda.

CSI CDT Study Materials – definitions of Addenda vs. Change Orders vs. Construction Change Directives.

When the specifications allow controlled substitutions, a substitution may be approved during the bidding period only if what?

An addendum is issued to all the bidders

The proposer of the substitution is notified in writing

The architect/engineer accepts the substitution during the pre-bid meeting

Specifications are revised and reissued to include the substitution

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-aligned, paraphrased)

CSI emphasizes fairness, clarity, and equal information for all bidders. When controlled substitutions are permitted during bidding, the procedure typically described in Division 01 and the Instructions to Bidders is:

A bidder or manufacturer may propose a substitution for a specified product within a defined time before bid date.

The architect/engineer reviews the proposed substitution and may accept or reject it.

If the substitution is accepted, it must be communicated to all prospective bidders in a formal way so that every bidder is pricing the same requirements.

The correct formal mechanism during the bid period for changing procurement documents is an addendum. Therefore:

A substitution may be approved during bidding only if its approval is issued by an addendum to all bidders.

This maintains a level playing field and prevents one bidder from having a private advantage or a different scope basis than others.

Why the other options are not sufficient or correct alone:

B. The proposer of the substitution is notified in writingNotifying only the proposer does not put all bidders on the same basis. CSI stresses that changes affecting price, scope, or products must be distributed to all bidders via addenda during the procurement phase.

C. The architect/engineer accepts the substitution during the pre-bid meetingEven if verbally accepted in a pre-bid meeting, it must be officially documented by an addendum. Pre-bid meeting minutes alone are not a proper modification of the procurement documents unless they are explicitly issued as part of an addendum.

D. Specifications are revised and reissued to include the substitutionCompletely revising and reissuing specifications is not the usual or efficient method during a normal bid period. Instead, CSI practice is to use addenda to modify the existing specifications. On larger changes, an addendum may include revised pages, but the key formal instrument remains the addendum.

Therefore, in CSI-aligned bidding procedures, a substitution can be approved during bidding only when it is issued to all bidders as an addendum, making Option A the correct answer.

Key CSI-Related References (titles only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – procurement process, bidder communications, and substitutions.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Division 01 sections on Substitution Procedures and Instructions to Bidders regarding substitutions.

CSI CDT Study Materials – controlled substitutions during bidding and the role of addenda.

How does the architect/engineer control the project cost when not enough information is available to make product decisions during the design phases of a project?

Alternates

Unit prices

Contingencies

Allowances

CSI identifies several cost-control tools used in specifications and bidding documents:

Alternates – provide optional changes in scope or quality that can add or deduct cost.

Unit prices – establish prices for specific items or quantities where exact amounts may vary.

Contingencies – funds reserved by the owner (in the project budget) for unexpected conditions.

Allowances – specified amounts included in the contract sum for items whose exact product, quantity, or selection is not yet known at bid time.

When insufficient information is available to make final product decisions during design, CSI’s guidance is that the A/E can maintain control over construction cost by specifying allowances. An allowance:

Is clearly described in the specifications or Division 01.

Provides a defined monetary amount (or quantity and unit cost) for a future selection (for example, certain finishes, fixtures, or equipment).

Allows the project to proceed to bidding and contract award while preserving cost control, because bidders all carry the same allowance values in their bids.

Thus the best answer is D. Allowances.

Why the other options are less appropriate:

A. AlternatesAlternates help manage scope and options, but they do not directly solve the problem of not yet knowing which specific product will be chosen. They are more about “add or deduct” scenarios than uncertain product selection.

B. Unit pricesUnit prices are used when quantities are uncertain, not when product decisions themselves are unknown. They are tied to measurable units (e.g., cubic meters of rock excavation), not to undecided product choices.

C. ContingenciesContingencies are normally an owner’s budgeting tool, not written into the contract in the same way as allowances. They help the owner plan for unknowns but do not provide a structured way in the specifications to carry costs for undecided products.

Key CSI Reference Titles (no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – sections on Cost Management and Design Phase cost-control tools.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Division 01 provisions for Allowances, Alternates, and Unit Prices.

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – “Methods of Specifying and Cost Control Provisions in the Project Manual.”

Top of Form

Bottom of Form

Which of the following should be avoided when specifying warranties?

Requiring or permitting a warranty that strengthens the owner's rights

Requiring minimum warranty coverage available for a particular product

Including language to require warranties extending beyond the contractor's one-year correction period

Relying on a warranty as a substitute for thorough investigation of a product and its manufacturer

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

In CSI practice (as reflected in the CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide and CDT study materials), warranties are treated as supplemental protection for the owner, not as a primary quality-control method. CSI emphasizes that the specifier should carefully research products, manufacturers, and performance history, and that the specifications should clearly define the required quality, performance criteria, and execution. A warranty cannot compensate for poor product selection or incomplete specification of performance and quality.

Because of this, relying on a warranty as a substitute for thorough investigation of a product and its manufacturer (Option D) is specifically contrary to CSI guidance. CSI’s approach is:

First: proper investigation and evaluation of the product and manufacturer (technical suitability, history, service, financial stability).

Second: clear, enforceable specifications stating performance and quality requirements.

Third: warranties as an additional contractual obligation, not a replacement for the first two.

That is exactly what Option D fails to do, so it is the practice that should be avoided.

Why the other options are acceptable in CSI terms:

Option A – Requiring or permitting a warranty that strengthens the owner’s rightsCSI allows and often encourages warranties that provide greater protection than the default legal warranties, so long as they are realistic, coordinated with the contractor and manufacturer, and enforceable. Strengthening the owner’s rights through clear warranty language is consistent with CSI’s recommended practice, not something to avoid.

Option B – Requiring minimum warranty coverage available for a particular productIt is normal in CSI-style specifications to state a minimum warranty duration or coverage (for example, “not less than 5 years” for roofing). This sets a clear baseline of expectations and is fully compatible with CSI guidance, provided it matches industry practice and project needs.

Option C – Including language to require warranties extending beyond the contractor’s one-year correction periodCSI explicitly distinguishes between the contractor’s correction period (often one year, as described in the General Conditions) and longer manufacturer warranties (e.g., 5, 10, or 20 years). It is routine and appropriate for specifications to require manufacturer warranties that extend beyond the one-year correction period, especially for major building envelope or equipment systems. CSI materials show these longer warranties as normal practice, not something to avoid.

So, under CSI’s Construction Specifications Practice and CDT body of knowledge, the clearly incorrect—and therefore “to be avoided”—practice is Option D: counting on a warranty instead of doing the proper technical due diligence and specifying performance and quality requirements.

CSI reference concepts:

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – chapters on warranties and product selection (discussing warranties as supplemental protection, not a substitute for proper specifying).

CSI CDT Study Materials – sections on Division 01, product selection, and quality assurance/quality control versus warranties.

What is a fundamental principle required to provide fairness in a competitive bidding process?

Bid securities provide protection to all bidders for unfair practices of others.

The bid shopping process provides the most beneficial pricing to the owner.

All bids are prepared based on identical conditions, information, and time constraints.

A minimum of three bids are required to assure sufficient competition.

CSI’s treatment of procurement and competitive bidding emphasizes that fairness and integrity in competitive bidding depends on one core principle:

All bidders must be provided the same information, at the same time, under the same conditions.

In CDT terminology, this is often expressed as ensuring that all bidders have identical bidding requirements, drawings, specifications, addenda, and time to prepare bids. When this principle is followed:

No bidder has an unfair informational advantage.

Prices are based on the same scope and conditions, allowing an “apples-to-apples” comparison.

The bidding process is considered fair, competitive, and defensible.

That is exactly what Option C states: “All bids are prepared based on identical conditions, information, and time constraints.” This is the fundamental fairness requirement in competitive bidding as taught in CSI’s CDT materials.

Why the other options are not correct in CSI’s framework:

A. Bid securities provide protection to all bidders for unfair practices of others.Bid security (bid bonds, certified checks, etc.) protects primarily the owner, not “all bidders,” against the risk that the selected bidder will refuse to enter into the contract or furnish required bonds. It is about contract assurance, not fairness among bidders.

B. The bid shopping process provides the most beneficial pricing to the owner.“Bid shopping” (where an owner or prime contractor uses one bidder’s price to pressure others into lowering their price after bids are opened) is explicitly recognized by CSI as an unethical and unfair practice. It undermines trust and is contrary to the fairness principle.

D. A minimum of three bids are required to assure sufficient competition.While owners often seek multiple bids, CSI does not define “three bids” as a fundamental fairness requirement. A fair bidding process could, in principle, have fewer bidders; the key is that each bidder is treated equally and given identical information and conditions.

Thus, in CSI’s description of competitive bidding, Option C captures the central fairness principle.

The owner's budget may not be adequate to pay for the entire project. What method is used to allow flexibility in the event that the budget is exceeded by the bids?

Cash allowance

Quantity allowance

Unit pricing

Alternates

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-aligned, paraphrased)

CSI describes several techniques in the procurement documents to manage cost uncertainty. When the owner is concerned that the project may exceed the budget when bids are received, the most common tool to allow scope flexibility is the use of alternates.

Alternates (often called “bid alternates”):

Are defined variations in the work (additions or deletions) that bidders price separately from the base bid.

Can be additive (additional scope that can be accepted if the budget allows) or deductive (scope that can be removed to reduce cost if needed).

Give the owner the ability, after seeing the base bids, to accept or reject alternates to bring the project within the available budget without redesigning the entire project.

This fits the scenario in the question exactly: the owner anticipates that the budget may be tight and wants a mechanism to adjust the final contract amount if bids come in high.

Why the other options are not the primary CSI method for this budget-flexibility issue:

A. Cash allowanceAn allowance is a set amount included in the contract sum to cover a defined but not fully specified portion of the work (e.g., artwork, specialty items). It helps manage scope uncertainty, but it doesn’t systematically provide a way to reduce overall cost after bids in the same way alternates do.

B. Quantity allowanceThis is a form of allowance tied to a presumed quantity (e.g., rock excavation). It addresses uncertain quantities, not overall budget flexibility in the bidding process.

C. Unit pricingUnit prices provide fixed prices per unit (e.g., per cubic meter, per square meter) for work items whose final quantities are uncertain. They are useful for adjustments after contract award as quantities change, but they are not the primary tool for adjusting total scope to meet the owner’s budget at bid time.

Therefore, the CSI-aligned answer for allowing flexibility when bids may exceed the budget is:

D. Alternates

Key CSI-Related References (titles only, no links):

CSI Project Delivery Practice Guide – procurement and pricing strategies, including alternates and allowances.

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Division 01 sections on Alternates, Unit Prices, and Allowances.

CSI CDT Study Materials – explanations of bid alternates and their role in controlling project cost.

Which term or word is appropriate to use in specification text?

Any

As per

As required

Work

CSI’s Construction Specifications Practice Guide and CDT materials provide clear guidance on appropriate wording in specifications. They stress:

Use clear, specific, and enforceable language.

Avoid vague, subjective, or nontechnical terms that create ambiguity and open interpretation.

Among the answer choices, “Work” is the only word that is appropriate and standard in CSI-compliant specification text:

“Work” is a defined term in the General Conditions (and often Division 01), usually meaning the total construction and services required by the Contract Documents, including all labor, materials, equipment, and services necessary to complete the project.

Because it is defined and used consistently, “Work” is an acceptable and precise term for specification language. Example usage (conceptually): “Perform all Work in accordance with…”.

Why the other terms are inappropriate per CSI guidance:

A. AnyCSI recommends avoiding “any,” “either,” “etc.” and similar words because they are non-specific and create ambiguity. For example, “provide any fasteners as needed” does not clearly define what is required and can lead to disputes and inconsistent interpretation.

B. As perThe phrase “as per” is discouraged in CSI-style writing. It is considered informal and can be replaced by clearer, more direct phrasing such as “in accordance with,” “according to,” or “as indicated in.” CSI advocates for concise, plain, and unambiguous English in specs.

C. As requiredCSI strongly cautions against phrases like “as required” or “as necessary” when they are not tied to a clear condition or reference. They shift the decision to someone’s judgment later, instead of stating the requirement explicitly. If something is required, the specification should state what, when, and under what conditions, rather than simply saying “as required.”

Therefore, in a CSI-compliant specification, the term that is clearly appropriate from the options given is “Work” (Option D).

Relevant CSI references (no URLs):

CSI Construction Specifications Practice Guide – Chapters on language and writing style for specifications (clear, concise, complete, correct).

CSI Practice Guide for Principles & Formats of Specifications – Guidance on defined terms such as “Work.”

CSI CDT Body of Knowledge – Sections on specification-writing best practices and prohibited vague phrases.

In which project phase would outline specifications be created in order to be used as a checklist for further development of the project documents?

Project Conception phase

Schematic Design phase

Design Development phase

Construction Documents phase

Comprehensive and Detailed Explanation From Exact Extract (CSI-based)

In CSI’s project delivery model, the level of development of specifications increases as the project moves through the design phases:

Project Conception – programming, needs assessment, feasibility; little or no formal specifications.

Schematic Design (SD) – conceptual design, basic systems and relationships; CSI now emphasizes Preliminary Project Descriptions (PPDs) as early, performance-oriented spec tools at this stage.

Design Development (DD) – selection and refinement of specific systems and assemblies; this is where outline specifications or expanded PPDs are used as a structured checklist for developing detailed requirements.

Construction Documents (CD) – full, coordinated section-by-section specifications in MasterFormat order, fully detailed to support bidding and construction.

CSI’s Construction Specifications Practice and CDT materials explain that outline specifications (or expanded PPDs) in the Design Development phase play a key role as a checklist and coordination tool. They:

List major assemblies, systems, and products by specification section.

Identify key performance and quality requirements in a concise format.

Help ensure that nothing is overlooked when moving into full specification writing in the Construction Documents phase.

Support coordination between disciplines (architectural, structural, MEP, etc.) by providing a common list of systems and materials.

Therefore, the phase where “outline specifications are created in order to be used as a checklist for further development of the project documents” is the Design Development phase (Option C).

Why the others are not the best fit:

A. Project Conception phaseAt this early stage, work is focused on needs, scope, feasibility, and budgeting. Specifications are generally not yet developed to the “outline” level; instead, information is more conceptual and programmatic.

B. Schematic Design phaseCSI increasingly promotes Preliminary Project Descriptions (PPDs) during Schematic Design, which are even higher-level and more performance-based than traditional outline specs. While some offices may start outline specs during SD, CSI’s standardized view places the checklist-style outline specifications more firmly in Design Development, when system choices are better defined.

D. Construction Documents phaseBy this phase, specifications are typically developed into full, detailed sections (Part 1–General, Part 2–Products, Part 3–Execution) rather than simple outline checklists. The outline specs or expanded PPDs created earlier in DD have already served their purpose in guiding the development of these full specifications and coordinated drawings.

CSI reference concepts: